The Work of John Mason Neale in Orthodox Hymnody

Searching for Fr. Joseph Honeycutt's blog, I mistyped, but before I caught my error, a headline caught my eye. This article by Chris Johnson (no relation, to my knowledge) documents the great deal we owe to the Rev. John Mason Neale — especially in the Western Rite, where his work lives on.

My namesake could have added that Neale also translated Orthodox liturgies into English, authored the two-volume Introduction to the History of the Holy Eastern Church, penned several other works on Orthodox Church hymns and personalities, and leaned heavily upon Eastern piety for his four-volume Commentary on the Psalms. JMN's lower-case-o "orthodoxy" was heavily influenced by the upper-case variety.

I am happy to reproduce the article on this blog in full, with the permission of its author.

(Though it should be clear to all but the most hyperventilating vagante, I am not presenting this outside article to hail Anglicanism; I do so to express my gratitude for Neale's having accomplished [and suffered for] what so many have failed to do or dubiously claimed to have done: translating legitimate Orthodox texts into English — well.) — BJ.

-----------------

The Work of John Mason Neale in Orthodox Hymnology

by Chris Johnson

From time to time throughout church history, a movement arises somewhere within Christendom to dust off the hymns of the earliest church to make them appeal to current ways and styles of worshipping. In the mid-1800s, one such movement took place through the work of a man named John Mason Neale. Many Anglicans in England and their American Episcopalian counterparts will be familiar with many a number of Neale’s hymns. And to some extent, nearly every mainline Protestant denomination has experienced reverberations of Neale’s work in their hymnology. The Lutheran Book of Worship contains twenty-one of his works; the 1991 Baptist Hymnal contains seven. Since Neale himself was Anglican, his work has had its most impact within the Anglican community. While hymn writers such as Issac Watts, Charles Wesley, and Fanny Crosby are well-known to non-Anglican American Protestants, a very important part of Protestant hymnology would not be in place today if not for the work of the lesser-known John Mason Neale.

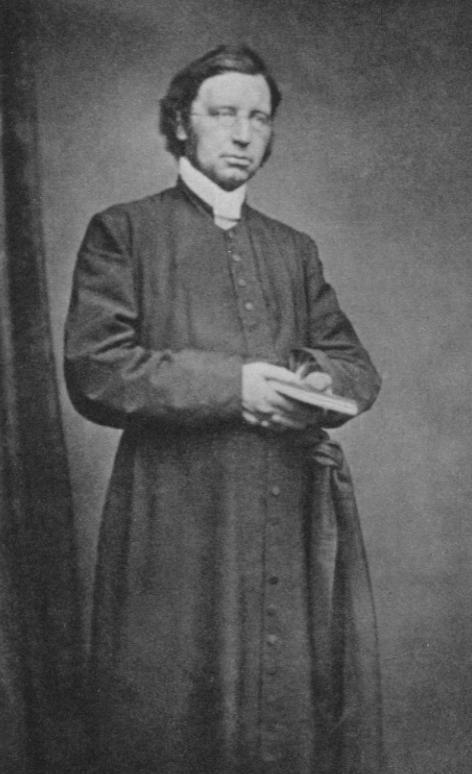

John Mason Neale

But the fact is, Neale did not actually write many hymns. His contribution was in the large body of early church hymns that he translated into the vernacular. Neale was arguably one of the most linguistically gifted people that ever lived; by the end of his life he had a working knowledge of at least twenty languages. This, coupled with his strong belief that the Church should not lose the richness and depth of early church hymns, resulted in his translating dozens of songs that would no doubt have faded into obscurity as historical Greek and Latin curiosities. As a proponent of high-church worship, Neale was by no means opposed to the use of classical languages for the hymns and liturgy. In this, he was motivated not by rebellion against tradition, but rather by the realization that early hymns and liturgies might in fact die out if not translated into the vernacular. As a result, dozens of early church hymns are still used in worship today.While doctrinal orthodoxy of belief was indeed a part of Neale’s legacy, it is the orthodoxy of the hymns that he translated which left a greater mark on the church. This influence is because Neale took great care in his translating to ensure that the truths presented in the hymns of the early church were carried over to the vernacular. Early hymns, particularly after Nicea, were often rich with orthodox doctrine. Not only were they sung as worship songs, they served as a tool for the church to carry out orthodox teaching to the masses. This stands in contrast to the main use of worship music today, which often serves the more singular purpose of simple praise. But the early church drew less of a distinction between these two realities (praise and orthodox doctrine)—orthodox truth was a statement of praise in and of itself. To the early church, an affirmation of the Trinity in song or liturgy was a powerful statement of worship. Indeed, in the heavenly worship we read in Isaiah and Revelation, it is the affirmation of the Triune God being given in praise to Christ in the form of Trisagion ("Holy, Holy, Holy"). The early church understood this well and considered orthodoxy and worship not as separate entities, but as one and the same. This would hold true for many aspects of orthodoxy such as the Incarnation and Christ’s con-substantiality with the Father.

Examples of Orthodoxy in Neale’s Translations

John Mason Neale recognized the importance of ensuring that these truths were carried over in his translations. The difficulty of accurate hymn translation cannot be overstated—not only is it typically impossible to maintain an original poetic rhythm in such a translation, a challenge also exists in the fact that hymns were originally written for a musical style that would be very foreign to modern Western music’s ears. The ability of Neale to maintain the integrity of the hymn’s orthodoxy, while also making into a "singable" form is a testament to his talents and determination.Neale made over 100 hymn translations, so there are many examples of orthodox statements carried over in his translations. While they all maintain Biblical truth, the hymns have varying degrees of richness and depth of doctrine. Some are rich with sweeping affirmations of orthodoxy, while others focus on more simple, less crucial realities. For example, "Jerusalem, the Golden" is filled with the imagery of heaven, which is indeed Biblically orthodox, but not necessarily an identifying and central truth of orthodoxy. And yet there are also many examples in his work of hymns containing key orthodox truths. In the well-known hymn "Christ is Made the Sure Foundation," we see the following:

Laud and honor to the Father,

Laud and honor to the Son,

Laud and honor to the Spirit,

Ever Three and ever One;

Consubstantial, co-eternal,

While unending ages run.

Neale maintains several orthodox truths from this 7th century hymn. There is the doctrine of the Trinity found in the first four lines. Then there is a statement in the fifth line declaring Christ as consubstantial and co-eternal with the Father and Spirit. The 6th line is a statement about the eternal nature of God as Trinity. These are all definitive truths of orthodoxy, originating with the church fathers.

In Neale’s translation of St. Ambrose’s 4th century "Aeterna coeli gloria" which in the vernacular is titled "Eternal Glory of the Sky," we find statements about the eternal nature of Christ, along with Christ’s redemptive work and status as the only-begotten Son. It also ends with a statement of the sinless nature of Christ as well as the virgin birth.

Eternal Glory of the sky,

Blest Hope of frail humanity,

The Father’s sole begotten One,

Yet born a spotless virgin’s Son!

Yet another example of the integrity of orthodoxy is in "Of the Father’s Love Begotten," a translation from a hymn by Aurelius Prudentius of the 5th century.

He is found in human fashion, death and sorrow here to know,

That the race of Adam’s children doomed by law to endless woe,

May not henceforth die and perish

In the dreadful gulf below, evermore and evermore!

O that birth forever blessèd, when the virgin, full of grace,

By the Holy Ghost conceiving, bare the Savior of our race;

And the Babe, the world’s Redeemer,

First revealed His sacred face, evermore and evermore!

In the first listed stanza above, we find statements about Christ as humanity—the incarnation, and the doomed nature of humanity due to sin. The next stanza reveals the virgin birth in the first line, along with the redemptive work of Christ. The last stanza of the hymn also contains a rich orthodox statement of the Trinity and final victory of Christ:

Christ, to Thee with God the Father, and, O Holy Ghost, to Thee,

Hymn and chant with high thanksgiving, and unwearied praises be:

Honor, glory, and dominion,

And eternal victory, evermore and evermore!

These are but a few of the examples of orthodox Christianity playing out in early hymns, and therefore becoming examples of orthodoxy being carried on to the more modern church. One can scarcely read the hymns of the early church without being struck by the reality that they were simply filled with the depth and richness of sound Christian doctrine.

Neale’s Own Orthodox Beliefs

As mentioned earlier, Neale himself penned only a few original hymns, but enough to give glimpse to his own orthodox beliefs. There is no doubt that Neale took orthodox doctrine very seriously and held to the very beliefs espoused by so many of the hymns he translated. He therfore recognized the importance of maintaining doctrinal integrity. In his children’s hymn "Christ is Gone Up," Neale demonstrates the truth of Christ’s ascension into heaven after the ressurection. He also writes of Christ’s "one holy Church." This is not unlike the affirmation of the one holy, catholic and apostolic Church found in the Apostle’s Creed.

Christ is gone up; yet ere He passed

From earth, in Heav’n to reign,

He formed one holy Church to last

Till He should come again.

And now we haste with thankful feet

To seek our Savior’s face;

And in the holy Church to meet,

His chosen dwelling place.

In his masterpiece "O Come, O Come Emmanuel" (really written by Neale although containing themes pulled from medieval sources), he affirms the incarnation as being the prophesied Savior to ransom the people of God thereby showing his belief in Christ as a sacrifice of atonement.

O come, O come, Emmanuel,

And ransom captive Israel,

That mourns in lonely exile here

Until the Son of God appear.

O come, Thou Wisdom from on high,

Who orderest all things mightily;

To us the path of knowledge show,

And teach us in her ways to go.

It is also noteworthy that He refers to Christ as "Wisdom," affirming the tradition of the church fathers in viewing the wisdom literature of the Old Testament to ultimately be pointing to Christ Himself.

Christian Service as Orthodoxy

There is another aspect to orthodoxy that comes through in Neale’s life and hymn translations: Christian ministry. The church fathers never really separated doctrine from Christian ministry. Basic Christian service as an aspect of orthodoxy seems often forgotten, dwarfed by the curiosities and theologies of doctrine which have an attraction all their own. The writings of the apostles, the Didache, is very much focused on Christian service, not so much doctrinal specifics which became organized and affirmed over time to defend against heresies. This does not mean, of course, that orthodox truths such as the Trinity were not always there, but rather that orthodoxy always held Christian service alongside doctrine.

Neale himself spent a great deal of his life in Christian service to the poor and needy, founding a Christian order of nurses called the Sisterhood of St. Margaret. The order provided the best nurses in all of England as was in great demand as a result. Its purpose was to "minister to the bodily, and then to the spiritual, needs of the sick and suffering poor -- going to their homes whenever called for, living with them, sharing their discomfort & refusing no difficulty, and adapting themselves to all circumstances." Through the founding and work of the Sisterhood of St. Margaret, Neale ministered to the poor, destitute, and poverty-stricken.

It is therefore no surprise to find hymns responding to the needs of human suffering among his canon of translations. Examples are "Jerusalem, the Golden,"—a popular hymn about heaven, "O Happy Band of Pilgrims" which offers encouragement to be steadfast, "Safe Home, Safe Home in Port" by Joseph the Hymnographer—a hymn offering solace and encoragement in Christ, "They Whose Course on Earth is O’er"—about eternal reward and deliverance from suffering, "We Have Not Seen, We Cannot See"—about walking by faith, and "Blessed City, Heavenly Salem"—another imagery-filled song about heaven. The obvious comforting message of such hymns for the suffering can be seen in the words of his translation "The Hymn for Conquering Martyrs Raise":

Fear not, O little flock and blest,

The lion that your life opprest!

To heavenly pastures ever new

The heavenly Shepherd leadeth you;

Who, dwelling now on Zion’s hill,

The Lamb’s dear footsteps follow still;

By tyrant there no more distrest,

Fear not, O little flock and blest.

These are not hymns sporting grand doctrinal themes (although they often contain doctrinal affirmations here and there), but rather offering spiritual encouragement for those suffering and struggling in their faith. It is a focus on service and ministry to the needy and the destitute. This is the other side of orthodoxy; an indispensable side espoused by the apostles and church fathers, but all-too-often forgotten and ignored by the modern seeker of orthodoxy.

Conclusions

The early hymns tell us a great deal about the early church, what they believed, and how early they were proclaiming their beliefs. Indeed, the orthodox truths confirmed at the Council of Nicea in 325 AD were already being sung "in the pew" long before. It gives great encouragement that orthodoxy was alive and thriving not just among clergy and the elite of Christian leadership, but flowing from the lips of the common people in worship services. It reveals itself as binding glue for the community of early believers; they sang orthodoxy with each other in worship.

But perhaps the most notable realization from all this is that through Neale’s translations, the work of the early church continues. The priority of orthodoxy by those Christian leaders of long, long ago remains effective because of the priceless work of Neale and others who have given great effort to accurately translate early church hymns. Neale has allowed the work of the early church to continue on into the 20th and even 21st centuries, because his translated hymns are still sung today. The early church recognized the need for its songs to be filled with the rich truths of God, even though they also taught those truths through verbal teaching and liturgy. In some unfortunate instances today, hymns and songs may simply be the only available means of modern Christians to receive orthodox teaching where such verbal teaching is lacking, so the importance of these translations cannot be emphasized enough. These early hymns contained the very truth of the gospel itself: the good news of the unsearchable riches of Christ.

Bibliography

Church, F. Forrester and Terrence J. Mulry. 1988. The MacMillan Book of Earliest Christian Hymns. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company.

Nelson, Dale J. 1997. John Mason Neale and the Christian Heritage. Mayville, North Dakota: Mayville State University; available from http://www.cyberhymnal.org/bio/n/e/a/neale_jm.htm

Project Canterbury. 1933. John Mason Neale. London: The Catholic Literature Association. Available from http://anglicanhistory.org/bios/jmneale.html

The Christian Praise Hymnal. 1992. Nashville, Tennessee: Genevox Music Group, Broadman Press.

The Hymnal Noted, Parts I & II. 1856. London: J. Alfred Novello. Published under the sanction of the Ecclesiological Society.The

Lutheran Book of Worship. 1978. Fortress Press.

Labels: liturgics

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home